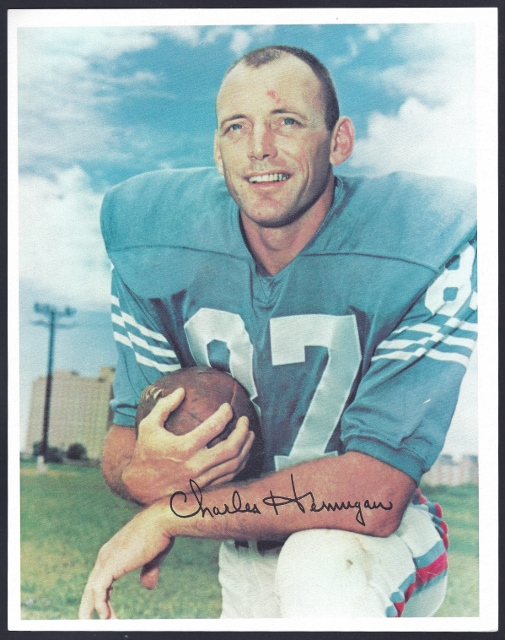

In researching and writing his fantastic book, Remember the AFL, Dave Steidel came to know many different legends of the American Football League. Charlie Hennigan is one of those men with whom he now maintains a friendship. Steidel penned (typed) this piece recently about the Houston Oilers perennial all-star.

I spoke with an old friend today whom I have never met, have only ever spoken to three times and yet, each time I have spoken to him has been for over an hour and with the feeling as if I have known him for a lifetime. He has so many memories about the AFL that I have always felt that I never had enough time, or focus, to truly do justice to our conversations.

Dr. Charlie Hennigan is a wealth of information about the American Football League. He has enough stories and antidotes about games and players to fill a book (he is currently working on his autobiography) and is always willing to share them with anyone who has the time and interest to listen. His serious side shares episodes about his early years trying out for the Edmonton Eskimoes and being cut, his many knee, shoulder and finger injuries that have made growing older more painful than it should be and his yearning to be recognized as one of the all-time greats by the Hall of Fame committee. His lighter side shares memories of having team jerseys stolen from the Oilers locker room, causing them to wear Dallas Texan ones to play an exhibition game against them, being carried off the field at half time with a concussion and then returning the field only to find himself sitting on the opponents bench and Lionel Taylor (whose pass catching record he broke in 1964) not giving him a warm blanket on a cold Pittsburgh night when Hennigan visited him because a playful Taylor told him, “you broke my record, so tonight I hope you freeze!” and Billy Cannon letting him out race him in his first training camp to make him look faster than he really was (and he already was pretty fast!). His unassuming, humble side that tells of his admiration and respect for George Blanda, and the two most influential coaches who he owes all of his accomplishments too, Mac Speedie and Doug Jones.

Hennigan loves to recall and talk about the glory days of the AFL. As I spoke to him from his home in Shreveport, Louisiana, the 78 years old Houston pass catcher is ever grateful for the opportunity to play professional football and reverent in his descriptions about the players he played with and against. His stories bounce around like an end-over-end punt rolling toward the goal line and his recall of events and plays are remarkably accurate and entertaining.

Hennigan’s AFL career began in 1960 when, after being cut by the Edmonton Eskimos out of college he returned to Louisiana to attend graduate school, did a stint in the Army and started his high school teaching career which paid him a little than $4,000 annually. The new AFL offered him another chance to realize his dream. Signed by Houston scout and Oakland Raiders coach-to-be Bill Conkright, Charlie recalls signing for a $250. bonus and an annual salary of $7,500. Upon receiving his first Oilers check he realized that the $250. was, in fact, no a bonus at all. It was only an advance, and was deducted from his first check.

As a halfback and track start in high school (he once held the conference record of 46.7 quarter mile) he was recruited by LSU where he matriculated after graduation. But after his girl friend passed away suddenly, Charlie, feeling alone and forlorn, left Baton Rouge and returned home to enroll at Northwestern Louisiana State.

As one of over 200 candidates trying to make the inaugural Oilers team, Charlie, a halfback and defensive end in college, was tried out at offensive end because he was too small to be a running back. But because he was now in uncharted territory, running new pass patterns and learning timing plays, and the fact that his small hands caused him problems catching throws, he was one of the players on the bubble as the last cut neared. Hennigan said he was only thrown around a dozen passes in college and remembers that during this first Houston training camp he had to change his pass catching style to compensate for his smallish hands and began cradling the ball rather than reaching to receive passes. It was around this time that LSU friend Billy Cannon lent a hand at trying to influence the Oilers decision. As the team was doing wind sprints near the end of camp, Cannon decided he was going to run alongside of Charlie and make him look faster than he already was by letting Hennigan beat him by a step or two each time. Cannon was a known entity and had already come to camp with the reputation as a speedster. When the coaches started seeing Hennigan edge out the LSU Heisman winner in side-by-side races they started to take notice. As the last cut neared the staff also noticed that Charlie was a master at getting open despite his shaky handling of throws. In an inter squad scrimmage late in training camp Charlie was consistently open and catching passes in front of future Hall-of-Fame defensive back and fellow rookie Willie Brown. As camp broke for the start of the first AFL season, Charlie was the last player to make the team. Brown was cut but quickly found a spot with the Denver Broncos.

His ability to get open and his football instincts to improvise did however get him in the dog house once during that first exhibition season. Learning his new position on the fly, during one early game the 25 year old rookie found himself covered tightly on a timing pattern that he felt needed to be improvised. So he broke off his charted course and headed to an open area on the field. But Houston quarterback George Blanda, under defensive pressure, was still on plan A and threw to where Hennigan was supposed to be. The pass ended up in the hands of a defensive back for an interception. Greeting Blanda on the sideline to explain his movement, Charlie learned a valuable lesson, as Blanda, the team leader, proceeded to ream him out, telling him that when he calls a play for his receiver to be in a certain place at a particular time, he damn sure better be there every time. Hennigan says he never forgot that lesson, and never again gave Blanda a reason to not trust him.

During his first season in Houston, Hennigan was third on the team in receptions with 44 catches, behind Bill Groman (72) and Johnny Carson (45) and played much of the season with a dislocated shoulder that was held in place with two screws. After playing for the iron-fisted Lou Rymkus in 1960, the Oilers second year saw former St. Louis Cardinals head man Wally Lemm take over after Rymkus was fired a few games into the season. Lemm, who Hennigan described as the best professional coach he played for, went undefeated the rest of the way and led them to their second straight AFL championship. He describes his second season as his best effort, even over his record setting 1964 campaign. He nearly doubled his receptions with 82, and established a new record for yardage receiving with 1746. Along with number 87 catching passes in Houston in ’61 were Bill Groman, rookie Bob McLeod and veteran of the NFL Bears, Willard Dewveall, who was playing on somewhat bad wheels.

Lemm left after the season so Hennigan and the Oilers showed up for the 1962 training camp with their third head coach in as many years. This time it was another former St. Louis Cardinals head coach, Frank “Pop” Ivy, who stuck around for two years before he too was gone.

Leading the Oilers into the 1964 was former New York Titans head coach Sammy Baugh, whom Hennigan described and the most disorganized coach he every played for. He described Baugh as a brilliant tactician, but that he was so intelligent about x’s and o’s that he would often confuse and lose his players during his chalk-talks which ended up being a quagmire of black and white crisscrossing lines among splatterings of Baugh’s tobacco juice.

As Hennigan prepared to begin his fifth professional football season in Houston he established a personal goal of breaking the AFL pass catching record of 100 receptions, set by Denver’s Lionel Taylor in 1961. He said that he took a bar of soap and wrote a big 101 on his shower mirror so that every day when he looked in it he come face- to-face with his goal. He also mapped out a plan for catching at least 7+ passes in each of the season’s 14 games. Starting on September 16, 1964 in San Diego, through the first 3 games that included Oakland and Denver, he was ahead of schedule, hauling in 24 passes for over 400 yards, and helping his team to an early 2-1 record. Then came a slight delay in his progress. Against Kansas City and Buffalo, both Oiler losses, Charlie caught only 6 passes – putting him 5 receptions off pace. Although Houston was in the middle of a team worst nine game losing streak, Hennigan was able to latch on to 8 passes against both New York and San Diego and then a even dozen against Buffalo, giving him 58 catches on the season and putting back on pace to break 100. With six games to go Charlie was within 3 catches of tying his 1963 total, and 43 away from his goal.

A trip to Boston’s Fenway Park was next, and although the Patriots were usually ripe for the pickings in the secondary, on November 6 they held the AFL’s leading receiver to only 2 catches. The Raiders secondary at Youell Field the next week yielded only 6 more, and with 66 passes in the books and four games to play, Hennigan was still 35 receptions away and would need to average nearly 9 passes per game to take Taylor’s record.

In Houston’s eighth loss in a row Hennigan caught 8 balls in a rematch with Kansas City. Then, as they hosted the same Patriot secondary that held him to only 2 catches three weeks ago, Charlie grabbed 12 on November 29 for 181 yards. With two games left, he had 86 catches, putting him 15 under his goal. The New York Jets visited next. With Blanda and Hennigan connecting for 7 more receptions, Houston broke into the win column for the first time since September and set up a climactic season ending game in Jeppesen Stadium on December 20 against none other than the Denver Broncos. To break the record Charlie would have to catch 8 more passes to reach 101, it he would have to do it in front of the record hold himself, Lionel Taylor!

By now Charlie was pretty banged up with sore knees, bruised shoulders and twisted fingers. He was regularly double and tripled teamed and says most teams would put a linebacker in front of him on the line of scrimmage to knock him off his course and then give way to two defensive backs to cover him. But Charlie was a man driven by his goals and was willing to do whatever it took to get to where he wanted to be. Playing for only their fourth win of the season the Oiler offense was well aware of what he, and they, needed to do to re-write the record book. Shortly before halftime Charlie reached his goal and cradled his 100th ball of the season, and then number 101! As the game was paused to honor his new accomplishment, both Taylor and George Blanda were called together to award him the record breaking ball. Charlie immediately handed it back to Blanda, thanking him for being part of the record and announcing that without George, there would be no record at all. That record breaking catch before halftime was his last of the season, although he does recall dropping a touchdown pass in the end zone in the second half of that game, which would have been number 102. The Oilers went on to win, 34-15, ending a disappointing season with a 4-10 record.

In 1965 owner Bud Adams was forced to bring in his fifth head coach, elevating assistant Hugh “Bones” Taylor to the top after Baugh decided to step down to become an assistant. With age, wear and the banging that he endured through five seasons now playing a role in Hennigan’s production, he fell off to 41 catches in Taylor’s first year and then to 27 in ’66. He knew he was at the end of the line and told management that he would not be back the next season. In spite of his announcement, the Oilers packaged him in a deal to San Diego to begin 1967. Always a man of conviction, Charlie reported as ordered, but upon his arrival told Sid Gillman that his better days were behind him, that his knees were shot, and that in his and the Chargers best interest, he was going to retire.

In his seven AFL seasons, Dr. Charles Taylor Hennigan caught 410 passes for 6,823 yards, 51 touchdowns, with a 16.6 yards per catch average; which breaks down to 58.5 catches, 974 yards and 7+ touchdowns per year. He played in every all-star game through 1965 and was named All-AFL in 1961, 1962 and 1964. He was undeniably one the most feared pass catches in AFL history.

The father of seven children and many grandchildren, Charlie says he is living comfortably in Shreveport, Louisiana, wants for nothing, and has a wealth of great memories of the AFL and the players he shared those glory years with. Still an educator at heart, he has written a program to develop personal excellence called “Set Yourself Free” and has taught it in several correctional institutions in his region. He also wrote a Bantam books novel called Slick.

As I ended our phone conversation and reflected upon the opportunity to talk with one of my boyhood heroes, it felt surreal. I had actually been talking to a player whom I watched on TV, collected football cards of, gave hero worship to and even morphed into many times on the playground as a youth. To me it also seems that the players from those AFL years truly knew what they had, are grateful for it and for the time they were able to play, and in fact played for love of the game. Charlie Hennigan is one of my many and favorite AFL memories while growing up, and I’m grateful that he remains a part of them as I grow older.

Charlie Hennigan: another example of a player who, in the view of the “pro football” hall of fame selectors, played in the wrong league. Had he played for the Cowboys instead of the Oilers, he would have been inducted years ago. (And the Cowboys might have won their first championship a lot sooner than 1971.) http://bit.ly/CharlieHennigan

Wonderful recap on a marvelous career. Charlie was indeed a player we (the Texans/Chiefs) had great respect for and made special preparations to play against. A shame not in the Pro Football HOF; neglected along with other great AFL players of the 60’s, Robinson, Haynes, Tyrer, Arbanas,Budde, Mays Powell, Sestak, Taylor (2), Faison, Grayson,Daniels, and many more et al.

‘Bias, the author makes a bad blunder. He refers to coaches Mac Speedie and Doug Jones. I believe Hennigan was referring to William (Dub) Jones, father of Bert and a Hall of Famer his ownself, from the Cleveland Browns.

rs

I want to find out more about the cold night in Pittsburgh… can’t wait for the autobiography. Btw: thanks Ange, Dave & Todd for all the great AFL stuff I never thought I’d get to see or hear about.

Thanks for the memories.

Great write-up ! ! ! Hennigan is undoubtedly an interesting man to listen to. Is this not part of Steidel’s book, “Remember the AFL?” (I hear people absolutely rave about that book.) The words “penned recently” in Todd’s introduction seem to indicate that this is not included in the book.

The Hennigan interview for this article took place on August 20, 2013

GREAT detail about L-Taylor telling Hennigan, “You broke my record, so tonight I hope you freeze.” Classic ! ! !

Really good chronicle of how Charlie chased Lionel’s record, and good detail about how Charlie and Blanda developed a connection.

This is also the first place where I’ve seen any explanation of why the great Sammy Baugh had a less-than-stellar coaching career.

Dave in 1953 Charleys senior year in high school, 46.7 in the 440 was near or at the National Scholastic record, the California State mark in 1953 was 47.1 set by the great Ollie Matson in 1948. In 1961 Compton Highs Ulis Williams set the track and field world on fire when he shattered the National record with a time of 46.1, a State record in the event that stands to this day. The previous State record was set in 1956 when Cochran HS sensation Jerry White ran a 46.7. I think only one prep ever broke 46 secs.

Charlie is also one of those men who gives everything he is in the service of others. My dad, Jim Norton, played with Charlie and was at dad’s funeral. One of the more honorable and kind men I have been fortunate to know.

Along with Hennigan other nationally ranked high school prep triack men beginning after WW2 and into the 1960’s that made it to pro football include: Hugh McElhenny 120 HH,180 LH 18.9, Jump Jump, Ollie Matson 9.6 100 & 47.1 440, Paul Lowe 18.7 180 LH, Marlin McKeever 61.5″ Shot Put, Billy Cannon 9.6w 100, Bert Coan 9.6 100 20.8 220, Jimmy Johnson 13.9 120 LH, Ray Norton 9.6 100, Ronnie Bull 18.9 LH, Tony Lorick 24’11” Long Jump, Henry Carr 9.3w 100 20.4 220w, Ray Poague 18.8 180 LH, Kent McCloughan 9.6w 100, Paul Warfield 180 LH 18.8 as a junior and 25′ long Jump as a senior. Gale Sayers 25’2.5″ long jump, Joe Don Looney 4×400 Relay 43.5, Mel Renfro 25′ Long Jump, Willie Williams 9.6 100, Dale Messer 9.6 100, Ron Snidow 190 Discus, Warren McVea 9.5 100, Houston Ridge 62.5 Shot Put, Wendell Hayes 18.9 180 LH, Tommie Smith 46.9 440 24’6.5″ Long Jump, Elvin Bethea 66’4.5″ Shot Put 186″ Discus, George Farmer 18.7 180 LH, Cliff Branch 9.3w 100, Mel Gray 9.4 100, 20.4w 220.

Notables missing from the list are Milt Campbell 1956 Olympic Decathlon Gold Medalist and Bullet Bob Hayes “The Wolds Fastest Man”.

I missed Walter “The Flea” Roberts 24’10” Long Jump and Luther Hayes 24.7 Long Jump, also Bert Coan along with his 9.6 100 & 20.5 w 220 Long Jumped 24.4 as a prepster.

Add Wayne Crow 179′ Discus, Jim Marshal 52′ 16 lb Shot Put and Jerry Tarr 13.9 120 LH. These were all high school times and distances. Marshall was not on the list of top 12 lb shot putters but made the 16 lb list in 1955.

Attempting to recall the pro football players that were ranked nationally in Track & Field in high school from 1947-1970 by memory is not fool proof, so I went back and reviewed the lists from Track and Field News and found some others including Earl “The Pearl” McCullouch Long Beah Poly HS 18.1 180 LH a record that stands to this day and 13.4 120 HH, Bill Staley 186′ Discus Las Lomas HS, Don Parrish 18.7 180 LH LA HS, John Harvey 48.0 440, Steve Holden 24.5 LJ & 18.6 180 LH Gardena HS, John Matuszak 180.5 Discus, Dave Butz 180.4 Discus, Issac Curtis 18.6 180 LH in his Junior year at Santa Ana HS, Rod McNeil 18.8 180 LH at Baldwin Park HS, Lynn Swann 25′ LJ Serra HS,James McAlister 25.6 LJ 18.8 180 LH Blair HS and Allen Carter 9.6 100 Bonita HS.

Clarence Davis 60.5 Shot Put LA Washington HS, Tom Reynolds 14’11’ Pole Vault Morningside HS and Sam Cunningham 62′.5″ Shot Put Santa Barbara HS were unranked nationally.

Last time I promise? Billy Howton Plainview Tex 14.3 120 HH, John Henry Johnson 57.4.5 Shot Put, Charlie Powell 57’10.5 Shot put, Don Maynard 14.5 120 HH 19.4 180 LH, Pete Retzlaff 162 Discus, Bill Forester 162 Discus, Bill Stone 9.7 100, Dick Dorsey 9.7 100, Ron Burton 19.1 180 LH, Billy Joe 59.1 Shot Put, Dewey Bohling 180′ Discus, Jim Marshall 168′ Discus, Billy Wells 14.1 120 HH, Richmond Flowers 13.5 120, Golden Richards 18.7 180 LH.

Billy Cannon as a Junior ran a 21.1 220.

One last time I think? George Buehler 61′ Shot Put and Stu Voight 67.75 Shot Put, On top of Richmond Flowers 13.5 120 HH he ran an 18.2 180 LH.

These like the previous are high school best times and distances.

Art Malone 18.7 and George Farmer La Puente HS 18.5 180 LH.

1959 Rudy Johnson Aransas Pass Tex HS 42.9 4×400 Relay, Tony Lorick LA Fremont was a member of the nations fastest 4×800 team 127.2 also in 1959.

Joe Childress 9.6 100 and 21.2 220. Odessa Tex HS 1952.

Rick Casares188’8.5 Javelin Throw, Jefferson HS Tampa, FL 1950.

Rosy Grier 194’2″ Javelin Throw and 57’2″ Shot Put, Roselle NJ HS 1951.

Rosey Grier, the iPad erased the e.

Andy Stynchula 166’10” Discus, 1956 Latrobe PA.

Ed Nutting 59’7″ Shot Put Northside Atlanta, Ga 1957.

Jon Arnett 127.6 880 relay, LA Manual Arts HS 1953.

Willie Hall 224’10” Javelin Throw, Pulaski HS New Brittain, Conn 1968

Terry Bradshaw 244’11” Javelin Throw Woodlawn HS Shrevreport, La 1966.

Charlie Smith 18.5 180 LH, Castlemont HS Oakland, Ca 1964.

Clint Jones 13.8w 120 HH, Cathedral Latin HS Cleveland OH 1963.

Paul Guidry 45’8.5″ Triple Jump, Breaux Bridge, La HS,1962.

Joe Orduna 120 HH 14.0, Central HS Omaha NE 1965.

Paul Gibson 120 HH 13.9, 13.8w, 18.9 180 LH Carlsbad NM.1966.

Larry Todd 880 Relay 126.1 Compton Centennial HS 1961.

“Travelin” Travis Williams 9.6 100, 21.0 220, Harry Ells HS Richmond, Ca 1963.

Woody Strode 120LH 54′ Shot Put LA Jefferson HS.1933.

Duane Allen 13’5″ Pole Vault Alhambra, Ca HS 1955.

Gene Washington” Vikings” 18.9 180 LH, Carver HS Baytown Tex.1963.

Bobby Smith 19.0 180 LH Compton HS 1957, that same year Chargers all time great Bobby Howard’s brother Junior set the National record in the 180 LH 18.5. Juniors record was eclipsed later that same season by Shafter, Ca HS Jesse Bradford 18.4.

Bradford would go on to play football and run track at Bakersfield JC and Arizona State where he was named All Border Conference twice in football and 220 Yard hurdles Champ.

What makes Bradford one of the more unique athletes is that he was and Offensive lineman at ASU played both tackle and guard, with the fact that he spurned pro football and enlisted in the Army out of college.

Former Lions running back Dan Lewis 21.0 220 Montclair NJ HS 1953.

1965 Kent Lawrence 9.5 100 21.0 220 Daniel Central HS SC.

1965 Ross Montgomery 9.6 100 Midland, Tex.

1965 Calvin Hill, 47′.5.5″ Triple Jump Riverdale, NY.

Steve Tannen 14.0 120 HH Southwest HS Miami, FL 1966.

Dwight Harrison 24’7.5″w Long Jump South Park HS Beaumont TX 1967.

Riley Odoms 6’8.5″ High Jump West Oso HS Corpus Christie TX 1968.

Delvin Williams 9.5w 100 Kashmere HS Houstom TX 1970.

Willard Harrell 24’3″ Long Jump Edison HS Stockton, Ca.1970.

Benny Malone 14.0 120 LH Santa Cruz Valley HS Elroy Arizona.1970.

Greg Pruitt 13.9 120 HH Elmore HS Houston, TX 1969.

Ed Buchanan 9.6 100 21.1 220 Kearny HS San Diego, Ca 1958.

Ed went from San Diego City College to the CFL and at one time held the CFL single season All purpose yard record, nearly 2100 yards in just 12 games with Sakatchewan.

Herschel Forester 161’2″ Discus Wilson HS Dallas TX. 1949

Herschel is Bill Forester’s older brother.

Earl Putman 56’3.5″ Shot Put Central Vocational HS Cincinatti OH 1950.

Putman played one season 1957 for the Cards and at 6’6″ 308 was at the time the largest player to ever play center.

Mack Burton 24’7.5″ Long Jump CFL BC Lions, Washington HS San Francisco, Ca 1957.

Bob Young 62’3″ Shotput Brownwood TX 1960.

Chuck Mercein 61’1.5″ Shotput New Trier HS Winnetka I’ll.

Mike Pyle 172’1.5″ Discus Throw New Trier HS Winnetka I’ll. 1957.

Bobby Howard 42.0 440 Relay & 126.2 880 Relay San Bernardino HS 1962.

Andy Livinston 21.4 220 (Turn) Mesa Arizona HS 1962.

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 2773 additional Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 80309 additional Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 39011 more Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 74494 additional Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/101-reasons-to-love-charlie-hennigan/ […]