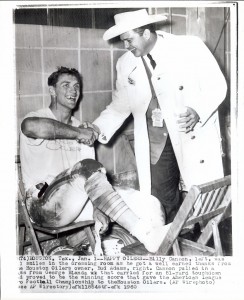

Yesterday we shared Dave Steidel’s study on the process by which Billy Cannon joined the Houston Oilers. Today Steidel takes a look at Cannon’s contributions on the field during his first few years of professional football.

Thanking Cannon for forging a path to the AFL for the many college stars who signed on may have come from the owners and the commissioner in their own way, but when training camp opened in July of 1960, there was no gift of thanks from the players, only the target to place on his back that marked him as the man to be measured against. As a media darling, the shifty, slashing 6’1″, 210-pounder was clocked in the hundred in 9.4 and was the scourge of LSU’s Southeastern Conference opponents for three years. Cannon was described in terms of being ‘faster than a speeding bullet and more powerful than a locomotive’ and because of the high profile law suit, everyone was aware of what his pay check looked like. It all became a source of envy for the new hopefuls in uniform who were out to impress their new coaches. Now it seemed like every defensive player in the league was out to show the two time All-American how “real football” was played, including his Houston scrimmage mates. More often than not during his first year he would hear comments from tacklers like “This is a different league, Cannon. You better grow up.” And when he fumbled in his first league game one opponent remarked “You’re playing with men now, All-American.”

From the get-go Cannon knew what he was up against, that everyone would expect him to act like a prima-donna and because of that he was consistently one of the first players on the practice and one of the last to leave. Cannon was determined to live up to his reputation as a player while also not showing any sign his unsolicited celebrity status. Admittedly, Cannon realized that he had a lot to learn about the game, saying he found out that what he didn’t know about football would fill a book and that he didn’t know how hard he could be tackled until he was hammered by the pros. He was introduced to the bell-ringing defensive tactic of being close-lined on pass patterns and for the first time was being asked to pass block, which he had not done during his storied college career. For Cannon, life in the pros had become a humbling occupation.

He was always aware of the high expectations people had of him, although those expectations were mostly unrealistic. According to Billy, you don’t run over the pros like you do in college nor can you out run the defensive backs or score touchdowns on every carry in the big leagues. Billy was more realistic, but occasionally also his worst critic, feeling like a phony at times when he would gain only a handful of yards during a game and then stand around afterwards signing more autographs than yards he’d gained. He was even benched in New York when he could muster only 9 yards on 6 carries. That was after gaining only 21 yards on 9 tries the week before against Dallas. Through the first half of his rookie year he was carrying the ball only 10 times a game and had yet to log more than 64 yards on an afternoon. He was also averaging only 1 pass reception a game while accounting for only 1 touchdown, a one yard plunge. It took until the Oilers eighth game of the season for Cannon to crack the century mark on the ground as he rushed for 105 yards on a season high 16 carries. But for the remainder of the year he would not go over 57 yards rushing.

By Cannon standards his 644 yards gained on 154 carries in fourteen games (a 4.2 yard average) was sub-standard. Yet only Abner Haynes and Paul Lowe gained more total yards and his 46 yards per game average was also eclipsed by only Haynes and Lowe. It took the AFL Championship game to raise Cannon’s spirits. Against the Los Angeles Chargers he gained 50 yards rushing and caught 3 passes, including a game clinching 88 yard touchdown in the fourth quarter that earned him the game’s MVP award.

The January 1 championship game seemed to rekindle Cannon’s fire. For the former LSU star, 1961 would see no sophomore jinx as the Oilers repeated as the AFL champions and Cannon raced to the top of the league in rushing with 948 yards and a 4.7 average. His pass catching skills were also revived as he nearly triple his catches in the second season, going from 15 in his first year to 43 receptions and more than doubled his touchdown total, scoring 15 times in ’61 after hitting pay dirt only 6 times as a rookie. And on December 3 in New York, he experienced his best game as a professional, establishing league records for yards rushing and touchdowns scored. Carrying the ball a career high 25 times Cannon ran for a record 215 yards, caught 5 passes for 114 and scored a league record 5 touchdowns. He followed up his record setting performance on the season’s last weekend by gaining 145 yards on the ground in Oakland to clinch the rushing title, and out gained the Titans Bill Mathis, the AFL’s second best rusher by more than 100 yards. It was the third time in the season that he ran for over 100 yards.

On Christmas Eve, Cannon proved to be the man to bank on again as he scored the AFL Championship game’s only touchdown on a 35 yard pass reception in the third quarter and earned his second straight championship game MVP award. Life in the pros had become more than being a marked man for Billy Cannon, he was a more complete player than the rookie who arrived with the Heisman, and while the target would still be on his back, now it would be because he was the league’s leading rusher as well as being a two time AFL champion.

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 64744 more Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 46381 more Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 68794 more Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-two-playing-with-a-target-on-his-back/ […]