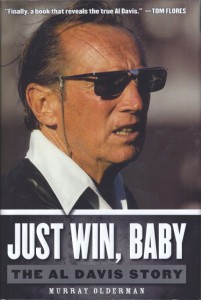

This time of year the shelves at local book stores bulge with new tomes pertaining to every theme in football – college, professional, biography, autobiography, strategy, important team/game, and on and on… Fortunately there are several interesting AFL-related books that have been recently released. One of them is Just Win, Baby; The Al Davis Story, by legendary sportswriter and cartoonist, Murray Olderman. I purchased this book last week, and had the opportunity to read it over the weekend. At just 202 pages, it is a fairly quick read.

This time of year the shelves at local book stores bulge with new tomes pertaining to every theme in football – college, professional, biography, autobiography, strategy, important team/game, and on and on… Fortunately there are several interesting AFL-related books that have been recently released. One of them is Just Win, Baby; The Al Davis Story, by legendary sportswriter and cartoonist, Murray Olderman. I purchased this book last week, and had the opportunity to read it over the weekend. At just 202 pages, it is a fairly quick read.

Murray Olderman begins the book with the story of how this biography came to be. Al Davis was interested in having his personal story written. He figured that fans across the country would want “to find out how we changed the course of pro football, and how the NFL is practicing revisionist history.” Davis contracted Olderman to write his biography, and put “no restrictions on subject material.” Scintillating stuff for sure, when you take into account Al Davis, and what he has meant to professional football since first joining the Los Angeles Chargers coaching staff in 1960. This promised to be the best of the Davis biographies, which brings me to my first problem with this book…

Olderman states that there are two unauthorized biographies of Davis, Just Win, Baby by Glenn Dickey, and Slick by Mark Ribowsky. There is, in fact, a third unauthorized Davis biography, Black Knight; Al Davis and his Raiders by Ira Simmons. At first I thought that the Simmons book must have simply been overlooked, and I was willing to give Olderman the benefit of the doubt, as copies can be difficult to find. My willingness to overlook the simple mistake was soon challenged, however, as I began to find more inaccuracies in the text.

After spending several paragraphs talking about former Chargers tackle Ron Mix, whom Davis first coached at USC, Olderman sums up Mix’s greatness by stating that, “Mix also was one of only two players elected to the Hall of Fame whose careers spanned the entire independent tenure of the AFL: 1960 to 1970. The other was Lance Alworth.” Now there are a couple of things wrong with that statement. First, there were more than two Hall of Fame players whose careers spanned the entire AFL. Mix is one, but George Blanda, Jim Otto and Don Maynard also hold that title. You will notice that I failed to mention Lance Alworth. That is because Alworth came to the Chargers in 1962, and did not play the entire 10 seasons of the AFL.

It is common knowledge that Al Davis was a member of the early Chargers coaching staffs, and as such, he was responsible for courting and signing many of the top collegiate players that became Chargers. Perhaps his greatest signing was the legendary flanker, Lance Alworth. Olderman discusses Alworth joining the Chargers on page 55. “Because the Los Angeles market in 1960 didn’t respond to two pro franchises, just as it hadn’t in the days of the old AAFC with the defunct Dons competing against the Rams, owner Barron Hilton moved his franchise to San Diego for the next season. With Alworth joining San Diego’s receiving corps as an immediate sensation and acquiring the nickname “Bambi” for his deer-like leaps, the Chargers were even better as a team in their new home and scored 396 points, third only to the Oilers and Boston Patriots, while losing only two games out of 14. But once again the Oilers beat them 10-3 in the AFL Championship Game.” Good stuff, but for one problem. Again, Alworth joined the Chargers in 1962, not 1961. Not only that, but he was injured early in his rookie season, and as a result played in only four of the Chargers 14 games that year. He was hardly “an immediate sensation.”

The other problem that I had with this book was that I expected a fresh look at the AFL/NFL merger, and likewise information that would be new to football historians. Frankly, this book tells essentially the same merger story that is available in many other accounts. The lone bit of new information, perhaps, is that Davis was working in conjunction with Lamar Hunt on the merger. Essentially the two were operating separate flanks, both driving towards a similar goal. Other versions of the merger story suggest that Hunt had been meeting with Dallas Cowboys general manager, Tex Schramm, in secret, while Davis was leading an assault on the NFL by signing their top players to AFL contracts. Confirmation of their working together is nice to have, but truthfully, I think that most people had presumed that to be the case all along.

I don’t want to leave readers with the impression that this book is useless, because it is not. As stated before, Olderman had rare access to Al Davis, and presents his rise to power in a readable manner. I found Olderman’s account of how Davis came to be managing general partner of the Raiders to be the most clear and concise version that I have found. I am glad that I have added this book to my AFL library. However, I simply expected more out of a project that had such rare access to one of the most important figures in the history of the game. I wanted a fresh and in-depth look at Al Davis, and the decisions that he made to not only bring the Raiders out of the doldrums, but also to lead the two leagues to merge. What I got instead was basically the same account that I have read before, with a few cute anecdotes. It is unfortunate, because I believe that a book on Al Davis, along the lines of David Maraniss’s classic, When Pride Still Mattered, about Vince Lombardi, would be a truly phenomenal book, and an instant classic in the world of football literature.

Jerry Magee turned down Big Al, when Davis approached Magee about doing his book. Davis once cussed me out in the Chargers’ press box. I’ll tell you what happened sometime.

I’d lovd to hear the story, Rick! I’ll bet Jerry would have done a great job on the book. I’ve always enjoyed his writing.

Other clear and well researched authority can be found in “Lamar Hunt, A Life in Sports” by Michael MacCambridge. I’, 1/3 of the way through it as I write and thus far he appears to accurate in his research and writing. Chris Burford Texans/Chiefs 60-67

Thanks, Chris. That book is on my list. I just finished reading Walt Sweeney’s new biography, and have one on Gene Mingo up next. There is a book on the early Texans & Cowboys coming out soon, and of course, Lamar’s new biography. Lots of interesting AFL stuff to read!

I like your honesty in critiquing this book, Todd. You’ve made some good points in showing key facts misrepresented by Olderman. In his defense though, I can vouch on the difficulty of getting all facts 100% accurate when writing a biography. In my effort at authenticating Frank Buncom’s life, the biggest challenge is verifying dates, names, and how they all intertwine.

Nevertheless, as you indicate, Davis was a fascinating character and the book will get my attention.

Thanks!

Thanks, Buzz. I can overlook a certain amount of contradictory information when it comes to events that took place many years ago, and about which no one likely documented until years later. However, when a simple, easily confirmed stament is made and found to be false, then I begin to wonder just how much of the stuff that cannot be confirmed is false as well. Alworth’s rookie season, and the 10-year AFL players in the HoF is info that can easily be checked, if there was a question.

I can’t vouch for the full accuracy of Dickey’s book, but it was an excellent read and certainly seemed thorough.

I think Rick Smith could do a great book on the AFL!

I would buy it!

I attended one and viewed the other on tv those 1960 something LA Rams versus SD Chargers pre season games and I recall vividly the game I watched on tv and watched with baited breath Ron Mix throughly embarrassed and out of his league when faced down, head slapped and run around by The Minister of Defense Deacon Jones. Ron Mix would have been a good to average NFL tackle, that’s it.

I read Mark Ribowskys book slick. Good book. Heavy on early information. One thing i have yet to know for sure is did Davis pay $18,000 or $180,000 to buy into the Oakland Raiders ? I have read both numbers. If it was 18 it might be one of the best deals ever if 180 still fantastic considering the Raiders are probably worth around a billion dollars today.

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 17446 more Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 4400 more Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 41164 additional Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 35014 more Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 32254 additional Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 14860 more Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/just-win-baby-a-book-review/ […]