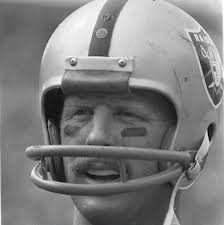

Rod Sherman joined the Oakland Raiders as a rookie in 1967, went to the Cincinnati Bengals int eh AFL expansion draft, and then was traded back to the Raiders in 1969. As such, he was a part of several interesting parts of AFL history. Sherman recently caught up with Tales from the American Football League, and spoke about his life in the AFL.

AFL – Talk about the process you went through getting into the American Football League.

RS – In some respects it is hard to rewind my mind on what the rationale might have been on several key points, but I was a fifth year senior, drafted after my junior year. Professional football was just starting to become a reality in the minds of the consumer in the early-to-mid 1960s. It probably was more visible, than I even knew, because as a young kid, I was focused on playing every hour of the day. There were very few televised games at all. I don’t think anybody in the early-to-mid 1960s had “football player” on the radar screen the way kids do today. Part of that equation is the money involved, but that also is derived from the visibility. College kids are more aware. They are tuned into it. There is programming almost 24 hours a day. That was not the case in my time. I had been encouraged to do as well academically as I was doing athletically. I think that to a certain extent, I achieved that. I got both an undergraduate degree in finance and real estate from the USC School of Business, and I also got a master’s degree in education. Pro football was literally a one-year-at-a-time proposition. I was very competitive, and profession football was a natural extension of the type of competition that we had in college, specifically at USC where we were playing Oklahoma, Notre Dame, and a lot of other good schools on a regular basis. I guess part of my decision came down to geography. If I could stay on the west coast, then I wanted to stay on the west coast. The more I learned about the American Football League, I realized that they were far more of a passing league than was the NFL. You saw that with Sid Gillman in San Diego. Then when Al Davis left Sid Gillman’s organization and went to Oakland, you saw it in Al Davis’s organization. Though I had graduated from high school as a quarterback, and envisioned playing as a quarterback, once I got to USC, I was put out as a wide receiver, never to return.

AFL – Tell me about coming to the Raiders after leaving USC.

RS – USC’s prominence in football was based on people, and not on real estate. We had great coaches. I had great teammates. But there were probably six or eight community colleges in the state at that time that had better facilities than USC. In the springtime we had to share the track bleachers with the track team during out spring practice. Fortunately the track coach, Vern Wolfe, was a visionary, and he benefitted from a lot of guys coming onto the track team from the football team. O.J. Simpson and Earl McCullough two USC football players, teamed up with two USC track athletes to set a world record in the 440 sprint relay in 1967 or 1968. As it relates to facilities, as least in the spring, we were out on that track field and the javelin throwers, discus throwers, shot putters, would practice early and then we would take the field. But in the fall, and occasionally in the spring, we would be on a practice field out behind Rice Field and Hobart Field, which was the baseball stadium. Our baseball team, our track team, our swim team, were all winning national championships at a quicker rate than was the USC football team, but none of them benefitted from real first-class facilities. When we were practicing out behind the baseball field, behind the right field fence, for example, we would have one ear tuned into the P.A. announcer because if Fred Lynn was in the batter’s box, or any other prominent left-handed batter, we knew there was a pretty good chance that a home run ball would come over that fence and explode in the middle of our practice field. So there were several occasions where a play or a drill would be interrupted, because you heard the crack of a bat, looked up, and saw that a home run ball was coming our way. We didn’t have great facilities, and certainly the AFL didn’t have great facilities. The hierarchy with the Raiders was that we didn’t even have a practice field. We dressed at the stadium, jumped on a bus, and then a couple of days a week went to Chabot College, a junior college in Hayward, where they had a legitimate football field with hash marks, end zones and out-of-bounds lines. Goal posts, even. Then a couple of days a week we would go to a public park in San Leandro, where there were none of those things, and we would practice there. In that respect, our facilities were less than not only what I had in college, but less than what I had in high school and junior high school. But in my rookie year we won 13 games, lost one, and went to Super Bowl II. It taught me early in life that facilities are important but they are not the pivotal factor. If you’ve got good people, who are committed to working hard, you can make a lot of things happen.

AFL – What most impressed you when you first came to the Raiders?

RS – People talk about speed being one of the big differences in the jump from college to professional football. I’m sure that is true. I was blessed with good speed, and that is probably one reason why I was drafted to play professional football. I ran track at USC, and I also played football. But you saw more speed just across the board. When I got to USC, we were literally at the end of an era of football players playing both ways – offense and defense. The mandate of playing both ways, I think, created a ceiling on player weight, which may have been 245-260. It is pretty tough for a guy to weigh more than that and be effective on both offense and defense. The passing game that I mentioned earlier was far more prominent and sophisticated at the professional level, as was all of the play-calling. The calling of blocking assignments, calling specific routes out of the backfield, in addition to what you wanted your receivers to do. Those are the things that I think impressed me the most. There were three of us that were about a month late getting to camp because of the game that they used to play in Chicago, the Chicago Tribune Charity Game, featuring the defending NFL champs versus a group of college all-stars. In the summer of 1967, I played in that game along with Gene Upshaw and Bill Fairband, also fellow Raiders. Within 10 years, that game was eliminated. I’m sure the NFL owners no longer wanted to expose the rookies to injury, as well as having their top draft choices out of camp for the first month of the season. Part of what impressed me was how the three of us had to step into a culture that already existed, and have to learn the playbook that had been put in. We arrived on a Monday and had an exhibition game the following Saturday, and we were expected to know the offense, or in Fairband’s case, the defense, and be productive. There were some very high expectations and we were not only physically doing double-day practices, but mentally doing double-day practices as well.

AFL – After your rookie season you went to the Bengals in the expansion draft. What were the challenges you found in playing for a first-year team. I would also be interested in knowing your comparison of coaches between Paul Brown and Al Davis.

RS – Technically, Al Davis wasn’t the coach, he was the managing general partner. But in reality, he was the coach. Similarly, Paul Brown was not only the coach, but he was the general manager, he was the president, and he was one of the owners of the Cincinnati Bengals. I don’t know the exact numbers, but if we had 40-man rosters back then in the AFL, I believe every AFL team had to put up 11 names and make them available to the Cincinnati Bengals. Then as the Bengals chose one name, then I think the Raiders could freeze two others. There was some sort of formula like that. The net event was that we had guys showing up from all over the country. Paul Brown was as well-organized than any other coach that I’ve been around, but he was also far more bitter than any other coach I had been around. The stories went that Art Modell, the owner of the Cleveland Browns, was forced to make a decision between Jim Brown and Paul Brown, and Art chose to go with Jim Brown. The story we heard was that Paul Brown wasn’t fired. He was kept on the payroll of the Cleveland Browns, and then he spent the next number of years down at the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club, playing gin rummy and bridge. Clearly, the lesson that he learned was that the next time he got back into football, there was not going to be another Jim Brown in his organization. He made sure on a daily basis that nobody thought so much of themselves that they might become Jim Brown. We had the rookie running back of the year, a kid named Paul Robinson, out of Arizona State. Within two years, nobody had ever heard the name Paul Robinson.

I challenged people when the Bengal organization was 10-15 years old, to name a Bengals player that had become a superstar. The closest one that had that kind of potential was a homegrown quarterback by the name of Greg Cook. But he injured his shoulder, and I don’t know that he ever made a comeback. He could have been charted to be a superstar. This might be a biased statement, but then I think you have to go to a fellow USC Trojan, Anthony Munoz, to find a legitimate superstar with the Bengals. That is a long-winded way to say that playing football needs to be fun playing in the Bengal organization.

There was a unique opportunity… Bill Walsh had watched me play in college. I know that was why I was selected by the Bengals. Bill was my receiver coach. Getting back to Paul Brown being a great organizer, he was also a visionary. He was one of the first coaches to recognize the expanded role of the passing game. He was one of the first coaches or owners to hire a receivers coach as part of the offensive staff. Though I didn’t particularly like the tenor that Paul Brown set for the game, being associated with Bill Walsh was tremendous, and it was a year that I enjoyed. I laughed with Bill years later when we would see each other at a sports event or a charity event out west, I would say, “Bill, it took you nine years to get out of Cincinnati, and it only took me one year. Why are they calling you a genius?” We would laugh, and then we would exchange our favorite Cincinnati Browns and Paul Brown stories. I guess it is easy to look back on it and enjoy it.

Our 1968 season ended in Shea Stadium, playing against Joe Namath and the New York Jets, who were just a few weeks away from being the first AFL team to upset an NFL team in the Super Bowl. We had everything to gain and nothing to lose in that game. I don’t really know the statistics, but in my mind, I was the leading the receiver for the Bengals that day, having caught two hitch passes for about 11 yards. The height of my frustration lead me to let Paul Brown know that in getting ready for the upcoming draft, I would like him to not include me in his plans for the next season. He nodded, and we didn’t talk much. Bill Walsh called me a couple of weeks later, and almost whispering, asked, “Did you ask the old man to be traded?” I said, that we had met at Shea Stadium, and that was when I had asked him to trade me. He said, “In all of Paul Brown’s coaching career, nobody has ever asked him to be traded.” I sort of laughed and shrugged my shoulders, because I didn’t really care. That’s sort of a long-winded answer, but we won the same number of game as most other expansion teams, which is probably two or three. We played in the University of Cincinnati Stadium, called Nippert Stadium. They were still years away from building the new stadium. In fact, in the late 1990s, I was participating in an NFL owners meeting in Scottsdale, Arizona. I walked around a corner and literally bumped into Mike Brown, Paul Brown’s son. He looked at me and we were sort of equally startled to see each other. He asked how I was doing, and I said, “Well, Mike, I’m not doing too well.” He thought I was going to give him some long health reports or something like that. I said, “Mike, I know I am getting old when the stadium that we dreamed about playing in when we were all original Bengals, they not only have built it, but they are now tearing it down because it has become antiquated. I just really feel old.” We both laughed and had a good chat.

AFL – Then you went back to Oakland in 1969.

RS – After that call from Bill Walsh, I had a call from Paul Brown. He said that he wanted to follow up on that conversation we’d had in Shea Stadium. If you want to be traded, where would you like to go? He encouraged all of us to call him by his first name. So I said, “Paul, I was born and raised on the west coast. I would enjoy being traded to a west coast team.” That would have been Chargers, Raiders, Rams or 49ers. Then I immediately told him that if he traded me back to the Raiders, then I would retire. That was really the end of the conversation. He didn’t ask why or anything. But the guy that coached the Raiders my first season there was a guy named John Rauch, and he and I just didn’t get along. I didn’t want to play for John Rauch. Well, Al Davis fired John Rauch, and hired John Madden. Paul Brown never asked me why I didn’t want to go back to Oakland.

Anyway, back to my perspective, which I think is that same as most guys had back then. I had a college degree, and none of us were making big money, so virtually all of us had off-season jobs. I was doing market research for a land developer in Orange County. As you know, real estate in the late 1960s and early 1970s was phenomenal. I was really enjoying my job, and was happy. I’d played two years of professional football, and now was in business with some good guys, and was able to utilize my college major, so on and so forth. So I picture this as just after the fourth of July, but I got a call from our receptionist, and she said that John Madden was on the phone for me. A that point in time, I was 100% sure that this was one of my college buddies or one of my former teammates, calling just to give me a bad time about everyone being in training camp but me. I took the call, and was going to try to decipher who was making the call before he could sucker me in and embarrass me. I picked up the phone and heard this voice that sounded just like John Madden of the Raiders. In my mind I was saying, “Wow, this guy is doing a good impersonation.” Back then nobody knew John Madden or his voice from television, so I was thinking that this guy had Madden nailed down really well. He began speaking, and had this certain sense of urgency, which is a typical Madden trait. He wanted to know where I was. He said, “Why aren’t you here?” I paused and by now was pretty sure that it wasn’t one of my buddies pulling a prank, but I still had no idea why Madden would be calling me. I said, “John, I am here at my desk in Orange County. I got this great off-season job that has turned into a fulltime opportunity.” He interrupts me and says, “Rod, have you heard from Paul Brown?” I told him that I had not heard from Paul Brown in two or three months. He said, “Rod, yesterday we traded back for you. We ended our conversation by asking Paul if he wanted the Raiders to contact Sherman, or if he wanted to contact Sherman. Paul Brown immediately said that he would take care of contacting Rod Sherman.” To this day I have still not had another conversation with Paul Brown. That was just typical of a bitter man his comeback in professional football.

Now that everybody knows John Madden it is easy to understand this, but back in 1969, he was an unknown. I have a lot of fun, even to this day, asking even the most ardent Raider fan, what was John Madden’s head coaching experience prior to taking over the Raiders? Nobody knows. He was the head coach at Hancock Junior College in Santa Maria, California. The reason I knew that was that there was only three years of eligibility back in those days, so in your freshman year, everyone played freshman football. We had our own separate team, and the California universities would play each other, and then you would play a Marine Corps team, or junior college teams. So we played Hancock J.C. when I was a freshman, so I knew of him back in 1962. But Madden was not the highly visible, entertaining character that he is today, but there was something about his character that as a coach, he felt a whole lot of pressure trying to meet Al Davis’s expectations. But he also allowed us to have a lot of freedom and fun in the area of humorous events. Almost overnight football became fun again. And it was an era when the Raiders won a lot of football games. I think three of the four years I was with the Raiders, we were in the playoffs. As we touched on already, one year we made it to the Super Bowl, and another year we went to the AFC championship. That was the other phenomenon that was going on, it was the merging of the two leagues. I’ll bet if you went back to look at newspapers from 1966 and 1967, you would find that there was a huge debate as to what three NFL teams were going to lower themselves and take 10 steps backwards to become a part of the AFC during the merger. There were 16 NFL teams and 10 AFL teams, and they wanted to balance the slate going into the new league. There were huge debates and millions of dollars to be paid for the three teams to be moved into the AFC. The three teams ended up being the Baltimore Colts, Pittsburgh Steelers and Cleveland Browns. What was interesting was that two of those teams, the Steelers and Colts, both made it to the Super Bowl within the first six years of the game. But such was the perception of disparity between the two leagues.

Fantastic interview Todd! What an incredibly well spoken man Mr. Sherman is; I can feel his measured tone of speaking in the way you have written his words. I miss this old era of football. It just isn’t the same anymore. As Mr. Sherman mentioned, in that era the idea of being a “professional football player” didn’t really register so they had to pursue education and the like, and I really think it made for such a more balanced human being, as is clearly evident from reading Mr. Sherman’s words. Thanks for the quick jaunt thru history, I could read this all day.

Thank you, great blog.

Todd- I am ready for your third book with all of the AFL interviews! Great job, it has really brought back so many memories from my youth. Although much like Rod said, I am starting to feel old!

While Arizona State had many a great running back during Paul Robinson era he was not one of them, he attended The U of Arizona. Fred Lynn was in Junior High School in El Monte Ca in 1964, Rod may have been speaking of Big Bob Selleck, the 6’6″ Selleck, Tom Selleck’s older brother was the Trojans slugger in 1964.

Excellent interview ! ! ! I’d never even heard of this guy. Rod Sherman gives great insight into that time period of the 1960’s, when pro football was ascending to the top of the American sports scene. He undoubtedly was a lot of fun to talk to.

I saw Rod quartback John Muir H S to a victory over Arcadia H S on arainy nioght in the Pasadena Rose Bowl in his senior year of H S in the 60’s. He was clearly the best player on the field that evening.

Later one of the partners in a CPA firm I worked for helped Rod negoiate his first NFL contract. This was unheard of in those days.

I was living in the Turtle Rock area of Irvine in the 70’s when Rod got in a dispute with the HOA because he had a chicken wire dog run in his back yard. The lawsuit made headlines in the Orange County Register.

Rod march to his own drum.

I cheerled for Rod Sherman and his high school football team in the fall of 1965 and he made the team #1 in C.I.F. all the way to the play-offs, where

Muir High lost to El Rancho where he averted us being shut-out by making a 4th quarter interception and running it in for our only T.D. that night. I pole-

vaulted on the track team while he was a sprinter, and have followed his pro

football career through the years with interest, and it’s nice to know he turned out so well with his education and all. I didn’t know him very well and was afraid he might turn into a dumb jock all his life, but I’m happy to hear that he has done so well after football (and that I grossly underrated his intellect). I heard recently from my sister who keeps up with people from the past that he might have got problems from football concussions in his later years and I sincerely hope that these are just unfounded rumors and that

he is all right. I’ve always admired his athletic ability and wish him the best. It’s also nice to see that he loves dogs, as do I. I have a white cat, but wish someday to get a house with a big yard so I can own a white bull terrier. Anyway, it’s nice to read about him and reminisce about that high school football team I cheerled for that was so good mostly because of him. My

given name was Allan Tingey, but I hated it so much that I changed it to Jess Lincoln in 1973. If Rodney Jarvis should ever read this I’d like him to know

that it was his leadership of that team that made my senior year in high school one of the happiest years of my life. I gave up playing “B” basketball

to be a cheerleader (and probably football, too), and it sure was fun direct- the crowds that great team of his brought to each game. Lot of excitement and wonderful memories. I hope he gets better if concussions took some toll on him. I wish I had gotten to know him better. Jess Lincoln

Five from those 1961 CIF and LA City league teams produced NFL players, including Rod, Les Shy Ganesha, Jim Vellone Cal HS, Dave Adlesh Long Beach St Anthony from CIF, the remaining two were LACity School Leagues Don Horn Gardena HS and Mike Garrett Roosevelt HS.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article author for your blog.

You have some really good articles and I feel I would

be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load

off, I’d love to write some content for your blog in exchange for a link

back to mine. Please send me an email if interested.

Kudos!

Feel free to visit my webpage: plumber trade school (Yvonne)

Rod mentions that he ran track at Muir HS and had good speed, in 1962 Rod placed fifth in the CIF SS finals in the 220, in a year when Southren California produced four of the fastest prep sprinters in the country. Richard Stebbibs Fremont HS, two years later the 19 year old would win gold in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics as a member of the 4x 100 relay team, Forrest Beatty Glendale Hoover HS ran 9.4 100, 20.4 220 and 47.0 440 and was destined for track immortality when he severly pulled a ham string muscle after winning State beating Stebbins in the 100 yard dash. Beatty never reclaimed his speed but ran track and returned kicks in College for the Cal Bears, Vernus Ragsdale SD Lincoln 9.4w 100 & 20.3w 220 and Tommy Hester San Bernardino HS set the National Scholastic record in the 180 LH:18.3 and recorded 23.1 in the 220 LH the fastest time ever at that time. Hester and Colden Cain became the first teammate prepsters to break 19.0 in the 180 LH during the same season.

Rod was in fast company in 1962.

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 83660 more Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 38558 more Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 89013 more Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 58330 additional Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 33661 additional Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 32167 additional Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/rod-sherman-of-the-oakland-raiders-and-cincinnati-bengals/ […]