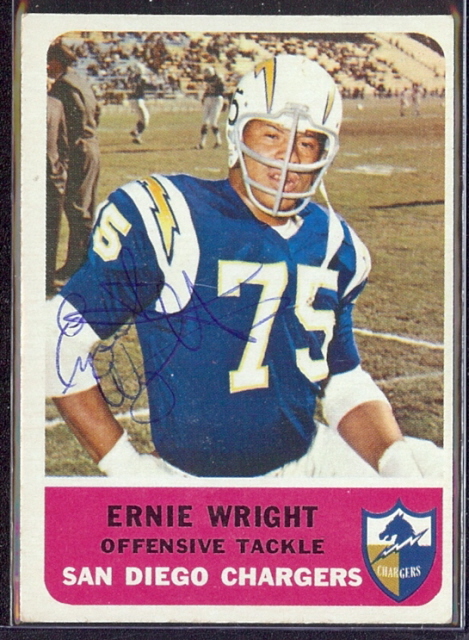

ERNIE WRIGHT

Offensive Tackle

Los Angeles/San Diego Chargers – 1960-1967, 1972

Cincinnati Bengals – 1968-1971

TT – Tell me about who scouted you and how you came to the Chargers

EW – Well, I came to the Chargers when I was a junior at Ohio State and out of school at the time. The old Ohio State coach was a friend of Sid Gillman. He said, “Ernie, would you be interested in playing pro football?” I said yeah. In those days you had to wait until the NFL draft. He said, “We’ll have somebody call you.” So then I got a call from Sid Gillman saying, “We’re starting this new league and Ernie Gottfried says you’re a helluva player, and he knows football. So I would like to talk to you about being a Charger.” So I subsequently flew out from Columbus to Los Angeles without an agent. I sat down in a room with Sid Gillman, Jack Faulkner, Al Davis and started talking about the new league and before I went home in about four days I signed a contract to become a player in the American Football League for the Los Angeles Chargers. I was married at the time, had one child and was expecting another one. It was, I don’t remember, a $500 or $1,000 signing bonus and a $10,000 contract. Of course they made it guaranteed for three years, $10,000, $11,000, $12,000. In those days, I know Jim Parker had been a great All-American at Ohio State. He was with the Baltimore Colts and he was only making $6,500 or $7,500 a year. I thought this was too good a deal to pass up. So that’s how I became a Charger.

TT – Were you at all concerned that the league might not succeed?

EW – Well, a guaranteed contract was just mentally it sounded good. But if the league folded or whatever, it wouldn’t have made any difference at all. If I hadn’t been able to play they would have found a way to cut me anyway, knowing how things work now. Concerned about the league folding? To a degree, but after my junior year I had been an honorable mention All-American. In those days we played both ways. I had been All-Big 10 or second team Big 10, I can’t remember. So I felt like I could play the game. It was fun to be going somewhere else. In fact, being from Toledo, Ohio, I knew more about the Cleveland Browns and Detroit Lions than any other teams. That would have been a fallback position. I was drafted after my rookie with the Chargers, in the NFL draft by the Rams. But to answer your question, I wasn’t concerned about it folding.

TT – What benefits were there in playing for the Chargers that you would not have gotten with any other team?

EW – I didn’t compare the Chargers to any other AFL team. I compared them more to the NFL. I think when I signed with the Chargers they had eight teams in the league. There were only 14 teams in the National Football League. There were certain things going on in the National Football League that we talked about because we weren’t thinking about the American Football League, but it would have been more of a concern if I had been drafted in the National Football League. For instance, we knew that as African-American players even then, that African-Americans didn’t sit on the bench. You had to be a starter. There was a quota system. They didn’t want to have over 10 African-American players; usually 6 or 8 because it would have been difficult on the road because you had to have a roommate. There was bullshit like that going on and we knew all about it. We knew all about it. It was not a National Football League. It was the game, but most of us felt that it would change to the game it was as you got more talent out there. The argument in those days was, “Is there enough talent?” If you go from 14 or 16 teams to 20 or 24 teams, is there enough talent? I don’t think that’s the problem. If you control who comes in, old buddy and good buddy. You want to win, but by the same token you want to carry on the tradition of George Preston Marshall of the Washington Redskins. There were some other factors that were part of football. And I’m not calling professional football back in ’59 and ’60 racist, but it affected baseball, football, basketball, and it still does to a degree. Not so much anymore. But I just always wanted to play in it and figured I was good enough to play in it. So I ended up coming into it. The other thing about playing for the Chargers, I didn’t know going into it… For instance, Sid Gillman, and he said this before, his first year he took all the good athletes and put them on offense, stating that if I score more points than you, then I am going to win. We didn’t win our first championship until ’63. And then I think in ’61 or ’62, I can’t remember, he started building a defense. Earl Faison, Ernie Ladd, they started building a defensive structure. Instead of having a team that was well balanced offensively and defensively, he said, “I am going to go for offense now and I will build defense later.” And that’s what he did. It’s fun playing the wide-open football game that the American Football League became where you throw the ball a lot, run tosses and reverses and so on and so forth. In many ways the National Football League was, “Let’s protect the ball, wait for them to make a mistake and we will win 13-10.” As opposed to playing a game and winning it 47-31 and that kind of stuff. We had a lot of fun playing football. The whole atmosphere was a lot more innovative and fun than the stoic National Football League.

TT – In 1960 the Chargers had three future Hall of Fame coaches on their staff. Did they show signs of greatness or appear overly impressive at the time?

EW – It was just another bunch of guys. See you have to remember, when we started in 1960 and 1961, we only had 33 guys on a team. And I looked it up, I think we had five or six coaches, total. So you have got less than 40 guys; you know everybody. You look at a team picture now, they’ve got a coach for the offensive right guard, the offensive left guard. You have got so many people that… You have got so many coaches that they kind of blend together. In our day all the players knew everybody and all the coaches knew everybody. I don’t think anybody could have predicted that Chuck Noll would have done what he has done. Chuck was a quiet guy, first of all. He was our defensive line coach. Pretty good in his technical ability on playing offense and defense because he played it as a collegian. Because in our days we played both ways. You didn’t just play on one line. When he left to go to Pittsburgh, it was like, “OK. He’s a good, solid All-American guy. He’ll do OK.” But to say that he would have won four Super Bowls, no. Al Davis, flamboyant, a kind of kidder-bullshitter. You took what Al Davis said with a grain of salt. He always wanted to appear and seem larger than life. But the story goes, and I don’t know if it’s true, that we would go into a hotel and he would go call the paging system and have himself paged so people would say, “Who is Al Davis?” But I see Chuck and Al now occasionally and they are great guys. I enjoy seeing them and meeting them. But I don’t know if any of them appeared to us players as being the future people that they have become.

TT – Tell me about Sid Gillman.

EW – We don’t have enough time. Sid Gillman the little bow-tied man. He signed me. He was my coach and general manager. There were times, especially in contract negotiations, that I couldn’t stand him, although I played for him. I couldn’t stand him, and I couldn’t hate him. I don’t know if you know what I am talking about. He was one of the first individuals that had me look at life as life. Life is not fair. You don’t live your life expecting other people to give you things. You have got to do it, you have got to take it. Eventually, after I got out of football and got into the agent business… Well after I got out of football I went on year into the World Football League. The team was supposed to be in Los Angeles then Mexico City, but they ended up back in Philadelphia. I was working with Ron Waller. I was the offensive line coach. We had to run some camps out here because you’re trying to find anybody that can breathe to play. I hired Sid to help organize my camp. So I went from being a player that he recruited and coached to hiring him and telling him what we were going to do. But I have seen him take a guy with limited talent and he’s such a great teacher, he was such a great teacher. He could show you how to run a pass route and become open just by this and that. He was a very technical person. He knew all aspects of the game. I had quite a time with Sid. Sid used to be a member of La Costa. I am a member of La Costa. Before he got to the point where he couldn’t move around, before he had his surgeries, he’d be down in the men’s locker room and he would always say what a great football player I was and so on and so forth. I said, “If I was so great, why would you screw me out of $1,000 back in 1962?” And he said, “Uh, that was my job and that was your job.” I have never thought of him as having a racist bone in him. You could room with anyone you wanted to room with. Although his first love was football, during the 60s, that’s when you had all the sit-ins and demonstrations. Some Southern cities were hopeful of getting pro football franchises. So a lot of things happened. Our first year we went to play the Houston Oilers in Houston. We stayed at the Rice Institute and we stayed in the dormitories. Everywhere else we were going we stayed in Hilton Hotels because the owner was Barron Hilton. And so we’re saying, “Why are we staying in these funky-ass dormitories?” Well, because the Shamrock Hilton is segregated. If you’re black, you have got to work there. That’s the only way you could get in there. “We ain’t coming here anymore. You can tell the commissioner that.” So Sid Gillman got on the phone and lobbied, and we never stayed anywhere but a Hilton after that. When we walked into the Shamrock Hilton a year later, the employees stood up an applauded because we were the first African-Americans to be guests at the hotel. Now I don’t think Sid did that because he believes in legal rights for everybody. He did that because he had some great African-American talent on his team and he wanted to put the team out there and he wanted to win. He did not try to bluff us or say, “We’re gonna cut you and so on and so forth. You better play or else.” He made things happen. We had tow other incidents. We had to play an exhibition game against the Jets in Atlanta. It’s hard to believe in this day and age. This was back in the early ‘60s. We stayed at the Hilton by the airport. We went to the mall next door to shoot pool. It was Ernie Ladd, myself, Earl Faison, Lance Alworth, it was about 12 or 15 guys, mixed half black, half white. Of course we were noisy wherever we would go. So we noticed that the kid running the pool rack would only give the balls and the cues to the white guys. We saw him get on the phone and after a while he came over and said, “I’m sorry.” It was kind of difficult for this kid, this young man who was working at the pool hall. But he had called his employer who said they didn’t allow any black guys. So we all left. We called Sid and said, “We’re not playing any exhibition game tomorrow in this racist damn place. This was at like 8:00 on a Friday, because we played the exhibition game at 8:00 on a Saturday. By 11:00 the Mayor of Atlanta and the Governor of the State of Georgia were in meetings with us at the hotel, apologizing and saying, “Please play and we will straighten this all out.” So you know the history of Atlanta and the Falcons and so forth. We had a year where we flew from San Diego to New Orleans to play in the all-star game, the AFL All-Star Game. The All-Star Game was supposed to be in New Orleans. We get in there at 11:00 at night and on the plane were guys from the Chargers and the Raiders. So we go to get a cab and the cab driver says, “No, you have to go over there to those cabs with the black cab drivers.” So here we go again. “We’re not playing in this place.” Now this is league-wide. So they move the game from New Orleans to Houston, the headquarters of the Shamrock Hilton. See how this stuff goes? So we play the game in Houston on five-day notice and New Orleans is out of the picture. The next god-dang year the all-star game was going to be in Houston. The airport is so fogged-in that we have to go to New Orleans and head back the next morning. We land at the airport and go over to the New Orleans Hilton by the airport. So we want to go down to the French Quarter. So we get in a cab. It is Dave Grayson, myself and Earl Faison. The guy says he’ll take us down to Acme’s or wherever we wanted to go. We wanted to go get oysters and all of that. And this was a black cab driver. So we started talking to him and he said, “Aw, I thought I recognized you guys. You’re football players, right?” “Yeah, yeah.” “You don’t know what you guys did last year. Now we have public accommodations on bussing and cabs. They can’t refuse people.” And so on and so forth. This city wants an NFL team so bad that they have changed years and years of segregated policies because they see something that they want. All of this had taken place during Sid Gillman’s time. Again, I don’t think he was motivated to do all of this because he was a clone of Martin Luther King, but he certainly didn’t disagree with it. And if it meant having a football team, he’d rather do it that way.

What else about Sid? Sid loved to play poker with us. We had a bunch of guys that would play poker and he loved to play poker. He was a guy that you could feel comfortable around. I also played for Paul Brown for four years in Cincinnati. Paul Brown might have sat at a table with me to have a formal dinner, but he was so cavalier and aristocratic. With Paul Brown you really had a chain of command and aristocracy with different levels. Sid wasn’t like that. He was one of the boys. I enjoyed Sid all my life. Probably one of the greatest minds in football. John Hadl was not a good deep thrower. So Sid Gillman came up with timing patterns. Five, six, seven-step drop. Take a seven-yard drop, John and throw the sumbitch as far as you can to Lance Alworth and see if he can catch it. Don’t wait until he’s open before you throw the ball 45 yards, throw it when he’s even with the guy at 20, and he’s going to catch it at 32 or 37 and he’ll out-juke the guy and out-run him. A lot of people didn’t want to do that. In my days of college football, you didn’t throw the ball to a receiver until he’s looking at you. You can’t do that today. If I throw that ball to you, and I have got to read and anticipate what you’re doing. I have got to throw the ball when your back is to me and the first thing you have to do is look for the ball because that ball is coming at you. He was more forward thinking. I don’t know who invented the forward pass, but he probably did more to make it as sleek as it is than anybody else that I have ever known. Great offensive mind. And a great guy.

TT – What do you think were some of Gillman’s drawbacks?

EW – He was a human being, like all of us. …Rough Acres. That was a pharse out there. If you could convince Sid that it was going to advance the ball 20 yards instead of three, he would take a chance on it. I also know personally, that in his life, that although he told me that football was a tough business, he had a tendency to look at things through rose-colored glasses. Ask him about Gene Klein. To do all that he had done for the Chargers and then for Gene Klein to treat him the way he did, I don’t think was very nice. But I was telling someone else, I think he was 91 when he died. I don’t think he’s got much to look back on and say, “Aw shit. I wish I had done this and this…” He was a good athlete himself. He coached in some great places, met some great people. I think he had a pretty good life.

TT – Tell me about Rough Acres.

EW – Well, it would be outlawed today. The Players’ Union would not allow anybody to live in such asinine, archaic conditions. They call is a practice field, but it was not a practice field, just some sand and chalk lines out there. The food was bad. It was hot. It was terrible. The thing I remember most about Rough Acres, I predicted going out there that we were going to have some bad accidents or somebody was going to get killed because Highway 8 used to be a two-lane highway. When you got passed Descanso, you had about a 12-mile stretch where you had three lanes. So if you got out on that third lane and nobody else would pull out to let you back in that’s front of you or coming towards you. Of course we would all get out in that lane and ride it for 12 miles and 90 miles an hour. Well, we were going 90 miles an hour one time and Lance Alworth passed us going 110. It is fortunate that no one got killed. But it was despicable. They say that we won the championship, but I don’t think that can be credited to Rough Acres. I think training camps can be too plush. I remember with the Chargers we started out at USD and there was a nice breeze up there. Usually you equate training camp with something more rural and something where you are getting down to the earth and you are getting your body in shape… I think there is a real need for training camp. Six weeks to get everybody focused. In fact I can see it being less than that now because you’re basically an 11-month player now. That’s what Parcells tells the guys in Dallas. “When you play for the Dallas Cowboys you are going to stay here and work out four days a week and I don’t care what the Player’s Association says. This is a fulltime occupation now.” In our day also, we weren’t making that much money, so we had off-season jobs. We worked in the off-season. Now you have offensive left tackles making $3.5 million. They should be fulltime. But getting back to Rough Acres in particular, it would have been shut down for how crappy it was.

TT – What did you think about Balboa Stadium?

EW – Well, you have to understand that I came from Ohio State. The smallest crowd I had ever played for was like 83,000. So I didn’t think much of Balboa Stadium. However, the stadiums don’t make it. I remember we played that first year in the L.A. Coliseum. I played in the Coliseum when I was at Ohio State, against SC. Our first home game I was introduced and we only had 17-or18,000 people there. It was a night game and we were still running out there with the light on and all that kind of stuff. You still get goose bumps and that kind of stuff. For a town like San Diego, it was OK. I did not like San Diego for years. I thought it was kind of a backwards, hickey town. I enjoyed the life in L.A. There was a lot to do up there with all the sports teams. Although we were the low man on the totem pole, we didn’t make any issue about that. Athletes are athletes. People, critics and fans and writers try to rank the leagues and the talent, but I remember sitting in a nightclub in L.A. The Cleveland Browns were in town to play the Rams on Sunday, because we were playing on Saturday. Jim Brown was there. It was basketball season. Wilt Chamberlin was playing for Philadelphia, he was there. They are all athletes and they were all talking. There are four or five major sections of the newspaper. There is a sports section. If you combine all the athletes in the world, I doubt there would be 10,000. So they are very cliquish and they know each other. I knew all the good football players because I played with them in all-star games and so on and so forth. We get to know each other. And you know somebody who knows somebody. So we came down to San Diego… We thought it was kind of slow down here. Not much to do. We’re not in the Navy, so good gracious. But obviously it has grown on me because I love it and I love living here, and I could live anywhere in the country that I want to live, but I like it here. We were excited when we moved into the stadium, San Diego Stadium we called it then. That was a major forward move. It was, probably in my mind… Franchise-wise, coming here in ’61 was a great move. Building that stadium, based on that vote, was another great move. That sort of kicked San Diego off into the big time, the major leagues.

TT – Did you stick around town in the off-season?

EW – Yeah. I had no aspirations of moving back to Toledo, Ohio. So I stayed here in San Diego, raised a family. Worked int eh off-season. I sold cars, worked construction. But I had no desire to return to my hometown Toledo or Ohio State. Even when I was in Cincinnati for four years, we maintained our home here. We moved the whole family back ther for six months and here for six months.

TT – Who were some of your friends on the team?

EW – Well, my roommate for years and years was Paul Lowe. My first wife and Paul’s wife, Sophie became great friends. When we moved here from L.A. in 1961, we lived in houses that were right next to each other. Two of our kids were born within 18 hours of each other. So Paul Lowe and I ran around a lot. Earl Faison, Ernie Ladd. I played a lot of golf with Sam Gruneisen, John Hadl, Lance Alworth. I say that would probably be the bunch back then. We did a lot of things together as families. My first wife has picture albums with all these people growing up together and now they’re having kids. We had some guys that hung together. It was kind of interesting too because being from Ohio, that was the first time I had dealt with Southern blacks or Southern whites. Take like a George Blair from Mississippi, Charlie Flowers from Mississippi. It was interesting getting to know these people and them getting to know us. Some of the stereotypical monikers that were attached to people disappear when you’re out there hot and sweating and showering naked and seeing who is doing what. You find out who you can trust and who you can rely on and who you can’t rely on. Because in the course of a game, there is going to be a chance to win and a chance to lose. There are some guys that will find a way to lose and some guys that will find a chance to win. If a guy is going to help you win, I don’t care what color he is, how his breath smells or what his thoughts are. If our whole society was more oriented that way as opposed to “I don’t like you because you are white. And you’re lazy because you’re Mexican, blah, blah, blah.” It gave me a chance to take a good look at the difference in people and races from all over the country. There are some African-Americans that were on our team that I did not associate with because I didn’t like them. I didn’t like they way they thought about things and I didn’t like the way they did things. There were some white guys that I felt very close to. And then golf has always had me out with the white population anyway. I was playing golf when I was 13 years old. I started caddying and playing golf. So I got used to being around the Caucasian population. It’s kind of funny. Even today, if you’re somebody, you’re not just black anymore, you’re a football player. It is just our society. My thing is that my friends are based on who they are, not what color they are. My friends today come from all walks of life and we may joke about racist times and so on and so forth, but it’s who you are, not what color your skin is.

TT – Tell me a favorite road trip memory.

EW – I don’t know if it’s a favorite. Remember I said I had a no-cut contract? In the first year of the Chargers, guys were coming and going like crazy. They would be here today and three people would be here tomorrow with the same helmet and same jersey. You wouldn’t know who in the Hell they were. We started out on the road. Our first game that year was down in Texas somewhere. I think the Dallas Texans. Then we were going to go to Buffalo. We took the bus from the game to the airport. There was another bus there. About 15 guys got off this bus and got on our bus. They called the names of 15 guys on our bus. They took 15 guys off our bus and they went back to San Diego when we went to Buffalo. So we were going to Buffalo and start practicing and there are 15 guys that I have never seen in my life before. It was a treadmill. You were always looking for players. The Ron Mix’s and Ernie Wright’s and Paul Lowe’s, the Charlie McNeil’s and some of those certain guys are going to be there forever. But the other supporting cast, they came and they went. We used to always have the Eastern swing. We would be gone for 17 days. Depending on who we were playing, we used to play a lot on Saturday nights. We would leave here on a Thursday and we would play the Titans, New York Titans, Boston and Buffalo. So instead of coming back, we would just go to the next place. We stayed in Lynn, Massachusetts, we stayed in Bear Mountain. I used to really enjoy going to Bear Mountain, New York. We would go down to West Point. It was quite a place. Of all places, we used to stay quite often at Niagara Falls, outside of Buffalo. We used to say, “Who in the Hell would have a football team stay in the Hotel Niagara for a week with nothing but newlyweds around here?” We’re practicing and horsing around, gambling and drinking. But that 17-day road trip was a lot of fun. We would get per diem for food. Some guys would spend more than they got, and some guys would come home making a profit. We had a guy named Henry Schmidt who used to bring a hot plate and canned beans to save money. We would have a big poker game going on the whole time where we kept score by paper and then the big argument was who was going to pay off the most money. We spent a lot of time together. Teams don’t spend a lot of time together anymore. You have so many specialists. We would have a team meeting and do a lot of things with everybody and then the special team meeting was everybody on the team because you participated on special teams. Then defense would go in this room and offense would go in that room. Now you have not only that, but you have a run cluster, a pass cluster, a pass-rush cluster. Today I don’t see them having the camaraderie that we had in those days… The guys that I remember the most are the guys that I played with before you had so many teams in the merger. Stories are rampant. Guys getting into trouble. Some of those stories you couldn’t print.

TT – What did you dislike about being a pro football player?

EW – Camps. After you’re there for four or five years, you know the offense. I only played for two teams my whole career. And being a student of the game because I was a coach for a while, I know what everybody did on every play. So to go into camp and twice-a-day do the same shit, after a while I would be like, “Well, I will leave my brain here, but my body is going to camp.” But it is needed for younger guys. It is kind of interesting. An example of camp being overrated, in 1970, I think, we had the first big strike. They were closing camps. I had always been active in the National Football League Player’s Association. I was a team rep for the Chargers for about six years. By the time I went to Cincinnati I was vice president of the American Football Conference. Jack Kemp was the president. When they merged the leagues, John Mackey took over as the head of the National Football League Player’s Association, and I was president of the American Football League. So I was pretty active labor-wise in those days. Although running four businesses now, I don’t want any labor unions coming at me now. We had a long negotiating session that cost the first exhibition game. Now during that time, we were talking about training camp and why I don’t like training camps. At this time I am an 11-year vet. So we agreed to terms in Rozelle’s office. Rozelle gives the player-reps an extra week to get their shit together before they have to come to camp. So I got back in Cincinnati for the second preseason game, which was my first. I didn’t play because I hadn’t practiced a down. I hadn’t played, except for staying in condition in the hotels, running up and down stairs and so forth, it had not been a year when I did my normal working-out. I went to camp and we started the season in two weeks and it was the best year I ever had as an offensive tackle. I don’t think I gave up any sacks. I graded in the high 90s in run, pass, cut-off blocks, everything. I did all that in two weeks. I was pretty rusty the first week, getting my timing going and all that stuff. But in two weeks I am ready to go. Why do I need six weeks? For younger players it is needed. If I were running a pro team in training camp, what I would do is, knowing that the guys are working out in the off-season, 10 months-a-year, three or four days-a-week, I would have a training camp where all my younger players and non-starters would come in for six weeks. I would take all my starters and older guys and I would bring them in a week or 10 days before the first exhibition game. You talk about training camps, and then you have four or five exhibition games. That’s just too much. And it’s the greed of the owners. I have four season tickets to the Chargers and I have to buy these funky-ass exhibition games. When I started we used to play them in San Antonio, Texas and these funky, little towns at fairs and that kind of stuff because none of the fans in New York or Cleveland or San Diego would come to the game. But they make them part of the package and now to keep the package you have to do it. Whatever the market can bear, but that’s the greed of the owners.

TT – How did your time with the Chargers compare to that with the Bengals?

EW – Starting with the Chargers it was a new league, wide-open and a whole lot of people. A very friendly atmosphere and so on and so forth. The Bengals and Paul Brown ran it very regimented. But I will say this, we were 8-8 our second year and we got to the playoffs. But we got shut down by the Colts. See any system can work, as long as it works. It is not that Sid Gillman’s philosophy wasn’t going to work or that Paul Brown’s wasn’t going to work. Both were committed to what they were doing. And by that time I was in my ninth year. So I am a professional now. Paul had a philosophy that players should be thankful that they were a Cincinnati Bengal. I had the reverse philosophy. You should be happy you have me because I can play on any team in the National Football League. A lot of guys don’t get that point, but a lot of guys do. You see it more and more on television when they get interviewed. There are guys out there that can play on any Goddamn team in the league. Once you know that, that’s when you are really productive because you know you are the elite among the elite. But you have got two different atmospheres going on there. San Diego weather here and the wide-open passing and so on and so forth. And back there it’s Midwest, hot, humid, ball-control. But you adapt. Having played in Toledo, Ohio in high school and Columbus in college, that weather didn’t bother me after you have a couple of weeks to get used to it. You adapt to it. I think athletes have a tendency to adapt quicker than most anybody else because you see so many changes and modifications. And that’s how I think we can, instead of going, “Oh my God, what do we do?” We’re going to change. We’re going to do it this way. It’s no big deal. They were two different ball clubs, and I think the big thing is that if you can sell a philosophy to your ballplayers and they believe it, it will work for you. And with the Chargers and the Bengals, we were able to do that.

I will tell you one thing about Paul Brown. Paul Brown was more like an old story about Bear Bryant. Bear Byrant’s philosophy way, “I coach coaches. My coaches coach players.” Sid Gillman coached everybody; players and coaches and so on and so forth. They had different styles. Sid Gillman was, “Roll up you shirtsleeves, get in there and get in done.” Whereas Paul Brown was like, “Here is what I want you guys to do. Now go out there and get it done. Here’s the game plan, go out and execute.” It was different.