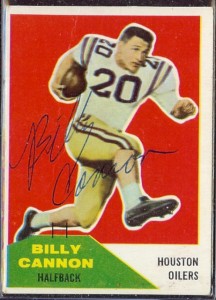

One of the most important of early American Football League players was Houston Oilers running back, Billy Cannon. In a two-part study, Dave Steidel takes a look at how Cannon came to the Oilers, and what he meant to the AFL.

When asked what one player, more than any other, saved the AFL from peril and brought it to the cusp of parity with the NFL, most people will answer, Joe Namath. When asked what one player put the AFL on the map, gave it immediate credibility and brought it more publicity than they could have imaged even before they played a single game, the answer has to be Billy Cannon, everybody’s All-American! He was my first favorite AFL player. Cannon was the 1959 Heisman Trophy winner and college football’s glamour boy, having led his LSU Tigers to the 1958 National Championship and authored the most talked about play of the season, his Halloween night punt return to beat Mississippi. Cannon was the biggest name signed by AFL in 1960 after Houston owner Bud Adams convinced him to sign with the Oilers and abandon the letter of intent he signed with Pete Rozelle and the Los Angeles Rams. The Oilers signing took place under the goal posts following the Sugar Bowl, his last game, setting off a war between the two leagues that would end up in the courtroom and put the AFL on the national media map. It would be the AFL’s biggest coup over the NFL after the senior league torpedoed them by first stealing one the founding franchises, Minnesota and then after both Lamar Hunt and Bud Adams did not bite on the expansion committee’s last ditch offer to squash the league by giving them the franchises they sought in the first place, dropped a new team, the Cowboys, in Hunt’s back yard.

The series of events started in Philadelphia’s Warwick Hotel on November 30, 1959, the day the Rams drafted him. In a 1960 interview with Furman Bisher for SPORT magazine Cannon’s recalled what transpired.

He was in Philadelphia to meet Rozelle after appearing with other college All-Americans on the Ed Sullivan Show in New York. Rozelle intended to sign Cannon to a contract and then date it for January 2, 1960, the day after the Sugar Bowl, there-by keeping him eligible to play on New Year’s Day. Rozelle, who by the end of January found himself in the NFL commissioner’s seat following the death of his predecessor Bert Bell, signed Cannon that evening for a $10,000 salary and another $10,000 signing bonus. The contract also called for the second and third years to be valued at $15,000 each. Not to be outdone, Adams contacted the LSU star when he returned to Baton Rouge and upped the ante, offering a personal services contract calling for $100,000 over three years. To Cannon, already the father of three young children, money was now talking and he changed his mind about running for the Rams and signed with the Oilers. With his attorney, Cannon sent a letter to Rozelle explaining he no longer cared to enter into any contract, “pre-dated or otherwise” with the Rams, returning all the money Rozelle had given to him earlier. He never got a response, but the gauntlet had been thrown and neither team, nor league intended to back down. The next time Cannon saw was Rozelle was at the Sugar Bowl when the Ram GM told him he would be contesting his decision in court. Lawsuits followed, and while Cannon was the biggest name courted by both leagues, he was not the only college player to sign on with the NFL and then change his mind for the AFL. Following Cannon’s lead, others who would sign with both leagues included Johnny Robinson, Billy’s LSU teammate, who signed with the Lions and the Texans; Mississippi fullback Charlie Flowers signed with the Giants and Chargers; TCU lineman Don Floyd with the Colts and Oilers and Ohio State fullback Bob White who inked contracts with the Browns and Oilers. But it was Cannon, the marquee player, who the NFL was going after for the breech.

In Cannon’s mind the contract he signed on November 30, 1959, was not dated and had no witnesses and therefore, not valid. When he saw the contact again after the Bowl game, the contract now had two witness signatures and a January 2, 1960 signing date. By having Cannon sign in Philadelphia, it was also contested that Rozelle had violated a league rule made back in 1926 by signing a college player before his eligibility was over. Cannon was quoted as saying “I don’t understand a football team that wants to force a boy to play for them against his will. It seems to me the Rams just want to keep me from playing anywhere, because I’m not going to play for them after all this.”

As it came to the pass the court upheld Cannon’s right to negotiate, saying the Rozelle had taken advantage of him and essentially voided the Rams contract, allowing the Heisman winner to play for the Oilers. Not only had the AFL scored its first victory over the NFL, it allowed the rest of the collegiates who signed with both leagues to make their choice again and gave fair warning that the American Football League owners had some fat wallets that were being opened to attract the best players, something the NFL had not been willing to do while operating its monopoly. With the Cannon decision, the war for players had begun and the NFL was significantly unnerved by their new competition.

In February, Rozelle met with AFL commissioner Joe Foss at a St. Louis airport to agree on a no-raiding policy and mutual respect for player rights. The new kid on the block suddenly had new found credibility and was being taken seriously. In all the AFL signed half of the top twelve players selected by the NFL in the draft and tallied 75% of the college picks both teams were after. Included in the heist were the star names of Abner Haynes, Paul Lowe, Richie Lucas, Ron Burton, Ron Mix and Chris Burford. The AFL was on its way, and had Bud Adams and Billy Cannon to thank for that.

This is great history that the NFL would like to forget….but it’s not the complete story – Clint Murchison also had Cannon signed to a personal services contract prior to to Dallas being officially awarded an NFL expansion franchise….The NFL had to sort out this dispute before it took on Bud Adams and the upstart AFL in court ….

Cannon became one of only twenty players who were on AFL rosters for the entire ten years of the league’s exitence. He also made the All-star team as a halback, and then as a tight end. If you’ve heard of another offensive player accomplishing that, I’d like to know who it is. http://www.remembertheafl.com/Raiders.htm#BillyCannon

A review of AFL signings from 1960-1962 shows that the league signed a disproportionate share of quality, known players. I’m not referring to black college players; which is a different matter. But the signings of big college players got the AFL off to a good start.

I meant Traditional Black schools, i.e. Grambling, etc, not African Americans per se.

[…] Cannon (shown), a Heisman Trophy winner who signed with the AFL under the goal posts moments after the 1960 Sugar Bowl (denying the NFL the right to sign him and sparking an interleague war), led the AFL with 948 […]

[…] Cannon (shown), a Heisman Trophy winner who signed with the AFL under the goal posts moments after the 1960 Sugar Bowl (denying the NFL the right to sign him and sparking an interleague war), led the AFL with 948 […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 75839 more Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 76315 additional Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 46536 more Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 31149 more Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 16293 additional Info on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 96386 more Information on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: talesfromtheamericanfootballleague.com/billy-cannon-part-1-the-war-begins/ […]